News Date:

Friday, March 7, 2025

Content:

Standing in front of a crowd of students and UC Santa Barbara faculty, Prof. Shelly Lundberg recently received a silver medal presented by Chancellor Yang for her achievements in economic research. Lundberg, a distinguished professor of Economics and Demography at UCSB, was honored with the Faculty Research Lecturer medal at the Corwin Pavilion for her groundbreaking work in labor, demographic, and family economics – particularly as regards gender.

“The Faculty Research lecturer is the highest campus honor the UCSB faculty can bestow on one of its members” said Chancellor Yang as he introduced Lundberg’s presentation.

Prof. Shelly Lundberg has been a part of the UCSB family since 2011, honored by the Economics department for her contribution to the field. Photo courtesy of UCSB Economics.

Lundberg revolutionized economic discipline by expanding our understanding of household dynamics. She introduced a model of understanding household decision making that took into account the differing goals of a couple. Her work carries importance in policy making such as the child tax credit, labor force participation, and childcare shocks in response to COVID-19.

Every year, the Academic Senate recognizes one individual for their work or research. Along with a medal and honorarium, each recipient gives a presentation. Originally awarded the honor in 2021, Lundberg’s opportunity to showcase her achievements was postponed due to the pandemic. The evening event also showcased one other past recipient, Richard E. Mayer, concluding with Lundberg.

Lundberg focused her remarks on the history of gender economic study, changing perspectives within her field, and her own opinions about the future of economic studies. She addressed the current challenges of gender bias facing both men and women in the labor market, advocating for a more inclusive approach to economic analysis. “Gender economics should not just be about women,” Lundberg said. “Men need some more attention.”

Lundberg received her B.A. in Economics from the University of British Columbia and a Ph.D. from Northwestern University. She joined UCSB in 2011. Serving as a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association, she is also the vice president of the organization as well as the chair of its committee on the Status of Women in Economics. She is a member of the AEA's Committee on Professional Climate and has served as president of both the Society for Labor Economics and the European Society for Population Economics.

Lundberg said that interest in women in the field of labor economics boomed in the 1970s. “The focus in labor economics previously had always been on the employment and earnings of men,” said Lundberg in her speech, as she explained how new data sets and analytical tools enabled economists to study women's labor supply more effectively. This interest also was spurred by a long-term upward trend in women’s involvement in the labor market.

Women tend to be studied in economics as a special category while men are treated as the default, she said. Lundberg dedicated much of her research to this previously understudied aspect of economics, recognized by the Faculty Lecturer Medal.

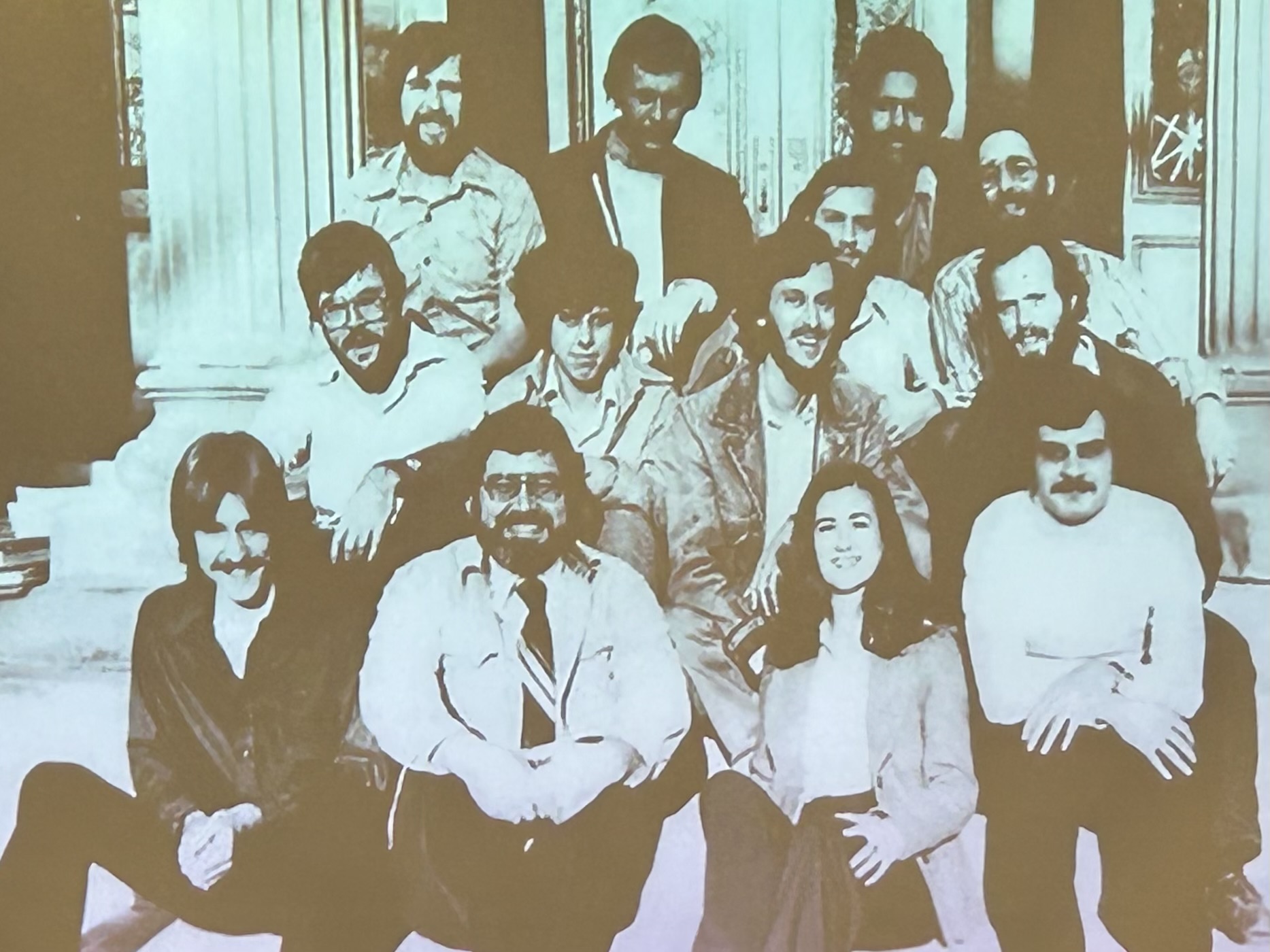

Prof. Shelly Lundberg’s surrounded by male colleagues early in her career, a photo she used in her presentation to point out her impact as an early female voice in the economic field. Photo courtesy of Shelly Lundberg.

Gender differences in economic behavior are primarily shaped by social norms, not innate differences, she said. Women’s labor participation, fertility rates, and gender role attitudes are strongly influenced by cultural transmission of these ideas across generations. Similarly, when boys underperform in education, economists often attribute it to innate skill deficits, but research suggests that social norms around masculinity play a crucial role.

“Economists have often been resistant to recognizing the role of discrimination, social norms, and power in shaping gender differences,” Lundberg said. She argued that mainstream economics must move beyond the assumption that market outcomes are inherently efficient and instead consider how gender norms and constraints may distort these outcomes.

Lundberg highlighted how economic policies can influence household decision-making and gender dynamics. “If you change who in the family has control of the money, you can change what the money gets spent on,” she noted. She pointed to historical examples, such as the UK’s 1970s child benefit policy shift that allocated payments to mothers instead of fathers, leading to increased spending on children’s and women’s clothing while decreasing expenditures on men’s clothing and alcohol.

Lundberg also stressed the importance of recognizing social influences and cultural factors in economic behavior, particularly regarding gender differences. The emergence of behavioral economics helped to recognize that “individuals have separate preferences, and they often have competing interests,” she explained. “When [social and cultural] forces are internalized, they actually affect our preferences and our objectives.”

Lundberg called for continued research and policy innovation to create more equitable economic systems. Her talk served as both a retrospective on the evolution of gender-focused economic research and a forward-looking vision for a more inclusive field.

Natalie Morse is a third-year Communication and Film & Media Studies double major. She wrote this piece for her Digital Journalism course.

March 7, 2025 - 1:30pm